Truth from models?

Over the course of the last 20 or so years that climate has been a topic of rapt attention we are frequently told what the “models” say. About the correlation between CO2 concentrations and average temperatures. About temperature and storm activity. And so on. I suspect the vast majority of people don’t really know what a “model” is.

A model is a series of mathematical equations. The equations include variables and constants. A variable might be population growth, or rainfall, or solar flux, or the concentration of carbon dioxide.

Models don’t have to be complicated. An example often used in university economics courses is the consumption of pizza. In the most simple version, you could posit that the lower the price of pizza, the more slices will be consumed. Then you would locate data on the price and the quantity consumed, do a regression, and find how much consumption changed as price changed. You could take another step, and look at things that are often consumed with pizza, such as beer. You could test to see how higher beer prices affect the consumption of slices. This is stuff you would see in an “introduction to economics” course.

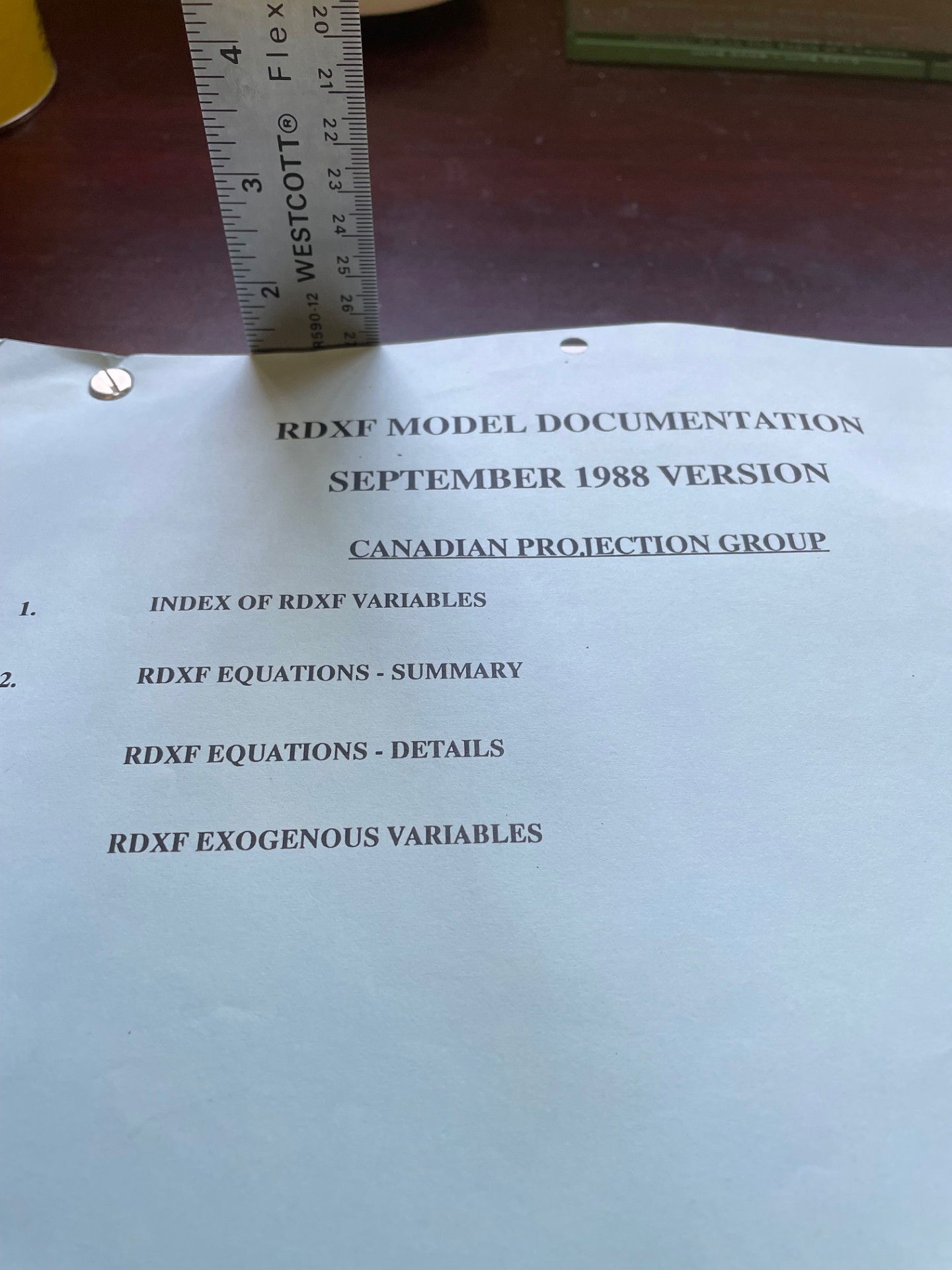

For my master’s thesis I modelled the influence of foreign exchange intervention on the real interest rate in Canada (the image above is from that thesis). I understand that this is getting into pretty esoteric stuff, so I won’t go into it further.

The Bank of Canada had a model for the Canadian economy developed over several years, and included the input of some of the top econometricians in the world. These models were called RDX1, RDX2 and so on. By the time I was responsible for some of the equations the model was known as RDXF. The model was run quarterly. It was a considerable allocation of resources, with dozens of Bank staff participating.

Note that this model attempted to explain and predict an entirely human creation, the economy. And it was fed high quality data which in itself had relatively little uncertainty around it.

Where is RDXF now? Besides the copy on my desk, and perhaps in some archive somewhere, it is extinct. Bank of Canada management eventually concluded that the results of the model did not justify the staff time and resources needed to maintain and run it.

Let me repeat – despite some of the best minds in the world helping to build it, despite the prodigious efforts of many very smart people (not me) to run it, despite the fact that it was trying to explain a completely human creation, RDXF just wasn’t that useful.

To a considerable extent the conclusions on climate change come from models. Climate is infinitely more complex than an economy. And the data these models are fed is nowhere near as straightforward as GDP or employment or prices.

One example – data on temperatures. We’re all familiar with weather reports saying “the high today was reached at 4:12 p.m. at the airport.” In some cases we might have two or perhaps three centuries of such data, such as for London. Questions about the data might include: Where were the temperature readings taken; Were the readings consistently either rural or urban; To what extent was the urban heat effect accounted for (pavement heats up more that grassy fields or boulevards, and there is more pavement all the time). There are hundreds of such questions around the data fed into climate models.

Moreover, a model is built to answer a question. The question is vitally important. Is it amenable to measurement and testing? Is the structure of the model appropriate? The output of the model depends on the model’s structure, and the modeler can, consciously or unconsciously, build in bias.

A joke my econometrics professor often told: What’s the difference between an artist and an econometrician? They both fall in love with their models. I suspect that quite a few people at IPCC are in love with their models.

I’m sure someone will say that computing power has grown exponentially since the 1980s – how can your experience from nearly 40 years ago be relevant? It’s true – my phone probably has as much computing power as the Cray “supercomputer” I ran my models on. What the Cray took hours to run can now be done in the blink of an eye. And today’s computers can handle infinitely more complex models.

But – does the complexity help? Do the builders even understand their models? Are the data robust enough to give meaningful answers? As every student knows: garbage in, garbage out.